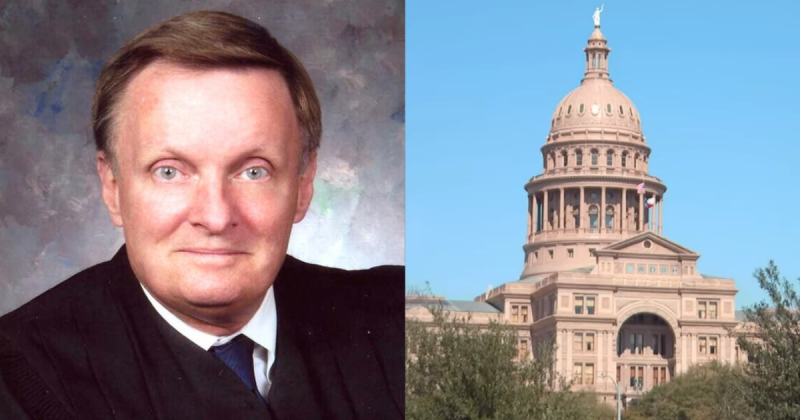

Federal Judge Jerry E. Smith has issued a forceful dissent in the case challenging Texas’s 2025 congressional map, criticizing his colleagues for what he calls a rushed and politically motivated injunction.

The legal battle erupted after a federal court blocked the map’s use just weeks before elections, amid claims it diluted minority voting power, even as Texas officials maintain it was enacted fairly and in line with state law.

The dispute has become a flashpoint in national debates over redistricting, judicial overreach and partisan influence in election administration.

Internal court communications show a multi-judge panel rushed the injunction with little regard for procedural fairness.

In his dissent, Smith contended that the majority opinion by Judge Jeffrey Vincent Brown amounted to “the most blatant exercise of judicial activism that I have ever witnessed.”

He noted that in his 37 years on the bench, he has never seen conduct like this.

“In summary, Judge Brown has issued a 160-page opinion without giving me any reasonable opportunity to respond,” he wrote.

Smith detailed the timeline.

After a nine-day evidentiary hearing concluded Oct. 10, Judge Brown and another member voted to grant the injunction, while Smith voted to deny.

On Nov. 5, Brown sent a 13-page outline to Smith, followed by drafts of 168, 161 and 160 pages over the next two weeks.

Smith argued the majority rushed its result.

“This outrage speaks for itself,” he wrote.

Smith also observed that the majority acted without waiting for his dissent and buried it in a separate docket entry, stating, “If these two judges get away with what they have done, it sets a horrendous precedent that ‘might makes right’ and the end justifies the means.”

Smith warned that the majority ignored the legislature’s role in redistricting, substituting judicial policy preferences instead.

Citing the Fifth Circuit, he noted, “[t]he most obvious reason for mid-cycle redistricting, of course, is partisan gain.”

He accused the majority of “judicial tinkering” with election laws on the eve of an election—a practice repeatedly cautioned against by the Supreme Court.

On the standard for preliminary injunctions, Smith stated that Brown selectively quoted precedent, omitting “substantial” from “substantial likelihood of success on the merits,” effectively lowering the threshold.

He also argued the majority improperly weighs factors, letting one dominate to the point of eclipse.

Regarding harm, Smith noted that the majority ignored the impact on Texas and local officials.

The injunction “is late-breaking … with disastrous unintended consequences for ‘candidates, political parties, [] voters,’ the State, counties, and local officials,” he wrote.

Smith further tied the ruling to outside actors. He singled out George Soros and Gov. Gavin Newsom’s (D) California political initiatives as beneficiaries.

“The main winners from Judge Brown’s opinion are George Soros and Gavin Newsom. The obvious losers are the people of Texas and the rule of law,” he wrote.

Smith asserted that several lawyers in the case are linked to Soros-funded organizations and referred to one expert as “a paid Soros operative.”

He also cited Newsom’s redistricting initiative in California as proof the decision favored partisan interests over law.

Smith contended that the decision is a political intervention, unsupported by doctrine and disrespectful of separation of powers.

He warned it hands a win “on a silver platter” to outside interest groups while leaving Texas voters and the rule of law as the losers.

As the case proceeds toward appeal, Smith’s dissent raises concerns about whether federal courts are overstepping their role in state election matters and whether judicial urgency is replacing deliberative justice.